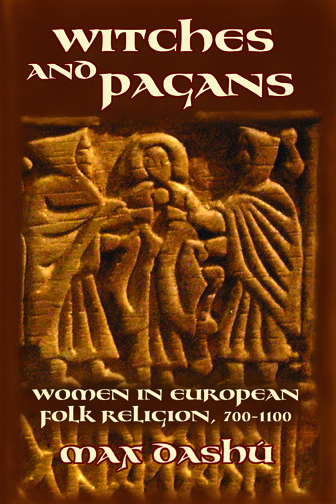

Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700-1100

A compelling exploration of language, archaeology, and literature that illuminates hidden cultural heritages: women’s ceremonies for the Fates; old ethnic names for ‘witch’ as wisewoman; the women who go by night with Diana or Holda. From forgotten heathen strands, the book reweaves the ripped webs of women’s culture. Annotated; 140 illustrations. $24.99 + shipping.

We are currently shipping to the US, UK, EU & CANADA. If you are outside of these areas or are looking to purchase a large quantity, please fill out this order request form.

$24.99

In this compelling exploration of language, archaeology, and early medieval literature, Max Dashu illuminates hidden cultural heritages. She shows that the old ethnic names for “witch” signify ‘wisewoman,’ ‘prophetess,’ ‘diviner,’ ‘chanter,’ ‘herbalist,’ and ‘healer.’ She fleshes out the oracular ceremonies of the Norse völur (“staff-women”), their incantations and “sitting-out” on the land seeking vision. Archaeological finds of their ritual staffs show that many symbolize the distaff, a spinner’s wand that connects with wider European themes of goddesses, fates, witches, and female power. They include Berthe Pédauque, also known as the “Swan-footed Queen,” whose spinning began at the proverbial beginning of time. Veneration of the Fates persisted under many titles, as the Norns, sudice, fatas and fées, Wyrd or the Three Weird Sisters.

Witches and Pagans looks at women’s sacraments in early medieval Europe, a subject that has been buried deep for centuries. Women set out offering tables for the Three Sisters or the “good women,” chanted over herbs, and healed children by passing them through ‘elf-bores.’ Spinning and weaving were ceremonial acts with divinatory or protective power, as bishops’ scoldings reveal. Churchmen also railed against the Women Who Go by Night with Diana or Holda or Herodias, in shamanic light on spirit animals. This was the foundational witch-legend that demonologists seized upon in later centuries. But witch persecution was already underway, as a chapter on the sexual politics of early medieval witch burnings documents.

A thousand years ago, an Old English scribe condemned people who “bring their offerings to earth-fast stone and also to trees and to wellsprings, swa wiccan taeca∂—as the witches teach.” This indicates that people still regarded witches as spiritual teachers, and that they performed ceremonies of reverence to Earth. Many aspects of ethnic spiritual culture survived the state conversions to Christianity: ancestor veneration, crystal balls, amulets—and witches’ wands. Artists depicted

Mother Earth giving her breast to serpents, animals, and children. Stories of ancestral women—the Cailleach and the Scandinavian dísir —were handed down over countless generations. Gathering together forgotten strands from heathen European heritages, Witches and Pagans reweaves the ripped webs of women’s culture.

Vol. VII in the series Secret History of the Witches