Additional information, photos, and corrections

Preface:

The nomenclature of knowledge in Western Civ relies on Greek words, from atom to zoology. Greek words are omnipresent in European languages: hero, charity, muse, museum, logic, theory, hypothesis, analysis, method, paradigm, dialogue; physics, atom, ergonomic, chronology, hypoglycemia, erotic.

Entire fields are named from Greek and derive the bulk of their terminology from it: philosophy, geography, geology, anthropology, biology, zoology, genetics, astronomy, mathematics, psychology, economics. Three fourths of medical terminology, for fields, organs, diseases and procedures, is derived from Greek, from adenoids to stethoscope to zoonosis. [www.ilekt.med.unideb.hu › kiadvany ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_medical_roots,_suffixes_and_prefixes ]. Greek letters are used in physics and mathematics.

Hellenic culture forms the foundation of modern Western Civ, and has influenced every corner of modern culture, from the architecture of church and state to unconscious assumptions about humanity, animals, and earth. Greek dominates the language of religion, especially Christianity: hymn, mystery, angel, diabolic, gnostic, prophet, epiphany, theology, exegesis, liturgy. Political science is loaded with Greek terms: democracy (and in practice, its conflation with slavery and empire), aristocracy, despotism, tyranny, hegemony.

Geography (“earth writing”) is studded with Greek mythology. Names of the continents Asia and Europe originate in Greek. The Atlantic Ocean was named for Atlantis, daughter of Atlas, after whom the Atlas mountains in North Africa were named. And later we get Atlantas not only in Georgia, but in 10 other US cities, along with Atlas in Michigan and Kansas, and Atlantic City in New Jersey.

European settlers named countless cities after places in Greece in the American colonies (such as Ithaca, New York, or Athens, Ohio, and Athens, Georgia, along with 14 other towns named Athens). There are countless Alexandrias, and several Corinths and Delphis. Just in the USA, there are twelve Arcadias and eleven Spartas. And many more examples here.

Hellenic names, especially mythic ones, are widely used for sports events (the Olympics, marathons) and even more so for brand names: Ajax, Nike, Trojans (creepy name for condoms once you think about it), Ford Mercury, Olympus cameras, Hermes scarves, the Amazon platform, and too many logo symbols to list, for example Hermes’ winged sandals or Pegasus.

Chapter I: Titanides

Re: Orphic Fragment 106

The phrase ἀμβρσίη Νὺξ, translated above as “immortal Nyx,” is also rendered as“ambrosial Nyx.” Immortality and ambrosia are etymologically the same in Greek: ambrosin. [www.hellenicgods.org/gaia—yaia—gaia, note 5.

- (99) σχόλιον Πρόκλου επὶ Κρατύλου Πλάτωνος 404 b (p. 92, 9 Pasqu.):

ὅτι ἡ Δημήτηρ, ὥσπερ πᾶσαν ζωὴν προχέει, οὕτως καὶ πᾶσαν τροφήν· ἔχει δὲ παράδειγμα τὴν Νύκτα,

θεῶν γὰρ τροφὸς ἀμβρσίη Νὺξ λέγεται

ἀλλ’ ἐκείνη µὲν νοητῶς.

“Wherefore Demeter, just as all life, pours forth, in this way also all nourishment;

and the paradigm is Nyx: ‘For it is said that the nurse of the Gods is immortal (ἀμβρσίη) Nyx’”

https://www.hellenicgods.org/orphic-fragment-106—otto-kern

“but in that way, accordingly, intelligible.” (tr. Van Kollenburg, citing Lobeck I 501)

Regarding the Proclus quote on 3rd page of Titanides: Nyx in charge of the entire world order “laying out boundaries” is comparable to Thetis laying out the posts of Poros and Tekmor, placing the world order, in the archaic poems of Alkman of Sparta.Some source, which I cannot locate now, claimed that Hesiod calls the goddess Gaia Pelori, Earth the Snake??? Maybe pylori: Greek pylōros : pylē, gate + ouros, guard, which would then signify“guardian of the portal.”

Snakes abound in the iconography of goddesses and female celebrants, held in their hands, wrapped around their bodies, rising up from the Earth between dancers holding fronds

James Notopoulos asks why Mnemosyne is named among the titanes, since she is a personified abstraction. [Notopoulos, 466] His commentary on the importance of Memory to the ancient culture of orature is well worth reading. One of the sources he cites is Plutarch On the Oracles of Delphi, who explains this relationship: “there is nothing in poetry more serviceable to speech than that the ideas communicated, by being bound up and interwoven with verse, are better remembered and kept firmly in mind. Men in those days had to have a memory for many things.” [Notopoulos, 469]

Notopoulos draws on the insights of Milman Parry, the great Homeric scholar, on oral poets “forging a metrical pattern which facilitated and guarded against mistake the information to be preserved.” [469] Parry saw “an oral poetry practiced by guilds of singers with masters…” using a characteristic diction with fixed formulas “ranging all the way from phrases of fixed epithet to whole lines and even whole passages. The outstanding feature of the formula in epic poetry is its repetition.” [470-71] As Parry put it, the poet drew on “word-groups all made to fit his verse and tell what he has to tell.” [471] He computed the massive number of repetitions in Homer, which ran to 250 pages. Similarly, a Serbian guslar could recite a poem the length of the Iliad. Krauss found one named Milovan who could recite 40,000 consecutive lines, and the top singers had a memory bank that could reach 100,000 lines. [472-73]

Plato in the Phaedrus presents an extended defense of the superiority of orature. He sets Theuth [Djehuti, Thoth], who Egyptians credited as the inventor of writing, against King Thaumus. “This invention, O king, will make the Egyptians wiser and will improve their memories; for it is an elixir of memory and wisdom that I have discovered.” The king retorts, You have invented an elixir (pharmakon) not of memory, but of reminding.” Thaumus tells Theuth that letters will give knowledge of doxa (thinking) instead of truth; they will become doxophoroi (carriers of ideas) instead of sophoi, (wise ones). [Notopoulos, 476-77; 483; citing Phaedrus 274e-275b]

Elsewhere Notopoulos quotes Plato on the problems of using words for wisdom teachings: “Acquaintance with it must come rather after a long period of attendance on instruction in the subject itself and of close companionship, when, suddenly, like a blaze kindled by a leaping spark, it is generated in the soul and at once becomes self-sustaining.” [Notopoulos, 488]

Maia, one of the Pleiades and mother of Hermes: Wiktionary gives maia as literally meaning “lady.”

Alternate translation of the chorus of Okeanid nymphs implorinh the Moirai to keep them from the misfortune of being raped like Io: “Never, oh never, immortal Fates, may you see me the partner of the bed of Zeus,” or subjugated by any other god. [Aeskhylos, Promotheus Bound 894]

Skylla, a sea monster, Cycladic sculpture, circa 450 bce

On Zeus Moiragetes, “leader of the Moirai,” Graves comments, “But his claim to be their father was not taken seriously by Aeschylus, Herodotus, or Plato.” [1955: 49]

Regarding Heraklitos’ belief that the sun was an invariable size, and if it oversteps that boundary, “the Erinyes, guardians of Justice [Dike], will find it out.” Another translator renders as the phrase as “the Erinyes, assistants of Dikē.” https://chs.harvard.edu/chapter/chapter-3-franco-ferrari-democritus-heraclitus-and-the-dead-souls-reconstructing-columns-i-vi-of-the-derveni-papyrus/]

Gantz notes that other famous slayers of kin went unpunished, and asks why the Erinyes “did not punish Agamemnon for the slaying of his daughter, or Atreus for that of his nephew.” [Gantz, 14]

Hesiod wrote that Pandora was made by Hephaistos, taught by Athena, given kharis and desire by Aphrodite, and a “bitch mind” and thievishness by Hermes. Zeus gave her a jar, not a box, through which he cursed humanity. [Works and Days, not Theogony, in Gantz, 156]

Chapter II: Archaica

The Linear B script, which Michael Ventris deciphered in 1952 with the help of Cypriot texts using some of the same characters.

The Minoans and Mycenaeans, sampled from different sites in Crete and mainland Greece, were homogeneous, supporting the genetic coherency of these two groups. Differences between them are only relative, viewed against their broad overall similarity to each other and to the southwestern Anatolians, sharing in both the ‘local’ Anatolian Neolithic-like farmer ancestry and the ‘eastern’ Caucasus-related admixture.” [Lazarides et al 2017]

The Greeks had become sea raiders, slavers, and mercantile colonists. On bondmaids grinding grain on millstones, this theme is repeated in medieval Irish and Danish literature, where they are the lowest of the low, and expected to be wrathful.

On Beekes’ fascinating discussion of the Tyrsenoi / Tyrrhenian / Etruscans, see my commentary.

Aeolic and epic poetry meter: Joachim Latacz suggests that Homer retained these old forms even when they did not scan in his own dialect: “In many cases the Ionian bards would have been able to replace these words and forms with metrically equivalent words and forms from their own dialect. This they did not do. Hence it is a widely held belief among Greek dialectologists that Mycenaean bardic poetry survived the collapse of Mycenaean culture either entirely or at least particularly vigorously in the Aeolian dialect of Greek, possibly passing only after an interval into other dialects, like the Ionian, with those Aeolian forms being simply retained.” [Latacz, 272]

Hellenic epic bards relied on set, often repetitive phrases, like the famous “wine-dark sea,” “ox-eyed Hera,” “swift Achilles.” These formulas acted as memory aids while enabling poets to keep to the metric pattern of dactylic hexameter. This rhythm was observed in the Iliad and the Odyssey—mostly. [Latacz, 252-3] Ionian had the peculiarity of dropping the “w” present in Mycenaean and Aeolian; similar changes happened with “r” and other sounds. Thi Ionian pronunciation introduced “errors” in the meter of the poem, but the poets went ahead using the more intelligible form for the archaic word, meter be damned. [Latacz, 261-6, details this irregularity in more detail.]

Miriam Robbins Dexter points out that the Odyssey contrasts the Phaiakian queen Arete with “those women / who now manage their homes / in subjection to their husbands…” because Alkinous honored her “as no other woman on Earth is honored.” [Odyssey VII. 66-68, in Robbins Dexter 1990: 111

For more on Helen and Penelope, see the section on Sovereignty in Miriam Dexter, Whence the Goddesses, pp. 146 ff. (This and other classic monographs are accessible via her academia.edu page). “These female figures represented and owned the land – they were the land.”

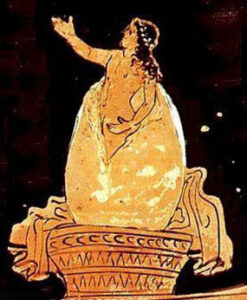

Helen born from an egg, laid either by Nemesis or by the Aitolian princess Leda

(after her encounter with Zeus in the form of a swan.

On Helen as sun goddess: Miriam Dexter, “The Assimilation of pre-Indo-European Goddesses into Indo-European Society” (On academia.edu)

On Danu/the Danaids, etc. See Miriam Dexter’s translations of texts in “Reflections on the Goddess *Donu” on academia.edu.

Re Danaides: Sieve-carrying was also the afterlife fate of people who had not been initiated, according to Plato and others. [Bonner 1902: 136-7]

It’s worth noting that Crete is as close to Libya as it is to Athens.

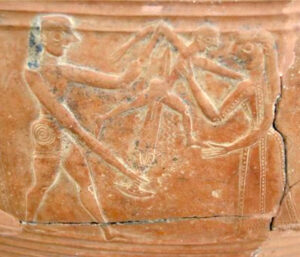

Mykonos pithos: A hoplite impales a woman’s son, but the artist shows a little smile on the mother’s face even as she is suffering a horrific war crime. Lack of empathy is a hallmark of patriarchal art; this same bland half-smile is also visible in depiction of atrocities in medieval European miniatures.

One of many war crimes depicted on the Mykonos Pithos

Briseis and Rape of Female Captives: Notes from Casey Dué (2002):

“The allusion to Mynes raises the interesting possibility that Briseis was the queen of Lyrnessos, and that her husband was Mynes. [36] If this interpretation is right, with this one detail the story of Briseis comes together and we can piece together her life as it is represented in the Iliad. She was born in Brisa on Lesbos, and married to King Mynes of Lyrnessos. [37] When Achilles went on his series of raids in and around Lesbos, he sacked not only Briseis’ hometown, where presumably her brothers were killed, [38] but also Lyrnessos. Achilles killed Mynes and enslaved the women of the town, winning Briseis as his prize.”

[She details variant traditions about Briseis, including this one from another old poem in the Epic Cycle, of which only fragments and a summary survive:] “In the Cypria, according to the scholia, Briseis was captured in a sack of Pedasos, not Lyrnessos, where we are told she was captured in the Iliad. [13]”

Dué then examines representations of Briseis in Archaic vase paintings. Some show “the traditional iconography of abduction,” while others present her in romantic or courtship scenes, holding a flower. She discusses the overlap of these two approaches, since the flower-holders in some cases are women, like Antiope or Helen, who were abducted. [Again, the romanticization of female captivity and sex slavery.] Dué thinks that romances about Akhilles and Briseis existed, and that in the Iliad she is a kind of “substitution” for Helen. Other traditions marry Helen with a now-immortalized Akhilles, living together on Leuke Island in the Black Sea. This may have roots in an old storyline in the Aethiopis, which ends with Thetis seizing her son’s body from the funeral pyre and taking him to that island. (So that her ceremony of conferring immortality on him as a baby actually succeeded.)

Next, Dué examines variant traditions about Briseis. In the Iliad, before Akhilles captured and enslaved her, she was born in Brise, Lesbos, but married out to Lyrnessos, probaby to the city’s king. In his book about the Trojan War, Diktys of Crete shows her as an unmarried daughter of king Brises of Pedasos, a city of the Leleges in Kilikia (Dardania). (But this account calls her Hippodameia, not Briseis.) The Akhaian warriors give her to Akhilles as a prize of war, along with another girl of the same age, Astynome, “because they could not be separated without much grief since they were of the same age and rank.” This is wild: they’re worried about the state of mind of girls who they will be serially raping for years.

A more ancient source, the Kypria, agrees that Briseis was from Pedasos, rather than Lyrnessos. Another possibility is that Briseis was connected with the town of Brisa on Lesbos, which also had a city Chryse. Dué explores the possibility that her story originated in Lesbos, in an Aeolian epic tradition that predates the Iliad and Odyssey. (This hypothesis aligns with the scholarship of Latacz, discussed above, which points to the more ancient Aeolic diction in those epics.)

Dué suggests that “the three different localities associated with Briseis—Lyrnessos, Pedasos, and Lesbos—are each connected with details that suggest different stories.” The story associated with Pedasos is reflected in later writings about a maiden Pedasa who falls in love with Akhilles and betrays her city to the invader. In one version she inscribes an apple, telling him: “Faint not, Achilles, till thou take the town: / Water has failed them, and they thirst to death.” In another she opens the city gates to let in the Greek army, only to see “her parents being torn / by bronze and the enslaving bonds of women / being dragged to the ships.” Supposedly Pedasa did all this so she could marry Akhilles, and be “wife of the best man.” (These verses are attributed to Apollonios of Rhodes.)

The tradition from Lesbos speaks of a beauty contest that also involved a dance. It took place in the common sanctuary of Messa, in the center of the island between the territories of several cities. One commentary refres to the kallisteia contest held in the Heraion. [scholia to Iliad 9.129]

Near the end of the epic, Helen wails: “So she spoke lamenting, and the people wailed in response.” (Iliad 24.776) Dué later comments on “the desperation speech, which [is] the particular province of barbarian or captive women.” Her commentary on kourai, “girl,” is illuminating. It is used for unmarried women, not only juvenile females, and even for married women taken captive in war.) “War prizes, in fact, seem to be eternal kourai, whether married or not. In the Iliad and Odyssey, women whose husbands have been killed revert to their father’s household: once widowed, they become girls again.” The suitors, presuming Odysseus to be dead, treat Penelope as a widow, and pressure her to return to her father’s house, only to leave it as a bride with one of them. [Odyssey 2.195-97]

Such women, widows or captives, are seen as returning to the state of nymphē, marriageable maidens. Even the word parthenos, translated to English as “virgin” (by way of Latin), is a renewable condition, as expressed in the myth of Hera recovering her partheneia in a spring. A parthenos can be a woman who has had sex, married, borne children, and become a widow. Similarly, “the word kourê, though it refers to an age class, may be applied even to middle-aged women.” It was a status marking availability for marriage, in a society that defines females in relationship to their fathers and husbands. Dué cites Sissa (1987) as showing “that Greek virginity was not understood in gynecological / physiological terms, but rather as a stage of life.” But it was also a state of being that could recur.

Dué agrees with Millman Parry, Albert Lord, Latacz and other scholars that the Epic Cycle cannot be the creation of one man, or even a group of them. “It must be the work of many poets over many generations. When one singer … has hit upon a phrase which is pleasing and easily used, other singers will hear it, and then, when faced at the same point in the line with the need of expressing the same idea, they will recall it and use it. But it is not enough to have heard the Iliad and Odyssey a hundred times. One must have heard hundreds of other tales as well. These hundreds of tales and versions of those tales form a backdrop of tradition every time a song is sung.” And she adds that the vase paintings representing these stories “are a visual representation of narrative.”

The storyline is charged with patriarchal politics: “Much of the meaning of the poetry comes from the interaction of the Briseis narrative with other traditional narratives: love stories of maidens and foreign enemies, the capture and destruction of cities, the carrying off of daughters, the loss of husbands, the enslavement of royal women.”

Dué makes one other interesting observation on the homoerotic element in the relationship of Akhilles to his friend Patroklos. “In later phases their relationship may have been understood to be that of erastês and erômenos.” These words mean lover and beloved, usually of an older man to a boy; but the sources don’t agree on which man was which. Akhilles I clearly younger, but his eminence points in the other direction in this hierarchical relationship.

For an analysis of Martin Bernal’s book Black Athena, which I discuss in Chapter 2, read more here.

It is very difficult to locate any analysis of Libyan archaeology in the bronze age, for the era before Hellenic domination. One source that looked promising was Knapp, Bernard. “The Thera Frescoes … Aegean Contact with Libyan LBA.” Journal of Mediterranean Anthropology and Archaeology, Greece, 1981, pp 241-71] But Knapp offers little or nothing on indigenous Libyan archaeology; he does not discuss a single artifact. His survey of Libya is very detailed geographic description, but without archaeological or historical info. He looks only at the Hellenic side, and reacts negatively to the observations by Marinatos, the excavator of Santorini.

Boaters in the murals at Akrotiri

Spyridon Marinatos noticed Libyan or other African elements in the paintings. He pointed to the youths’ hair lock, compared to Tuareg and Mauritanians (and we could add Kemetic as well). There are African fauna in the frescoes: panther, lion, and the horned Barbary sheep. [Knapp, 250] The African-appearing people in Theran murals must have prompted Marintos to explore this association, but Knapp never mentions them.

Herodotus says that Therans were moved to colonize Cyrenaica because of drought, famine, overpopulation. [Histories 4.15ff, in Knapp, 261] But Knapp concludes that there is “no indication of any Minoan, Mycenaean, or Cycladic artifact arriving in Libya during the Bronze Age.” [271] But he never considers the possibility of travel in the other direction, from Africa. The traditional date of the colonization of Cyrene is 631 bce. The settlers fought wars against the Libyans, who eventually lost, and were pushed back from the coastal lands. Their farming lands lost, they took to raiding their enemies.

The colony at Cyrenaica exported wood, wool, hides, wheat, olives, legumes, grapes, figs, produce, livestock. Sheepherding was well-established; Odyssey 4.85-89 refers to “Libya of the numerous flocks.”

For commentary on Martin Bernal’s Black Athena, I’ve made a separate post.

Chapter III: Goddesses Revised

Paired Archaic goddesses with plank bodies (p. 125)

Thebes, 4th c. bce, possibly depicting Demeter and Persephone riding in a cart

Here’s the 7th century “Rhea” enthroned with sphinxes, referred to on p. 125

On Samos the mating of Hera and Zeus took place for 300 years at a time. [Kerenyi 1951: 96] Other sources say it took him 300 years of wooing to be accepted.

Hera tells Aphrodite that she wants to visit “Okeanos, whence the gods have risen, and Tethys our mother, who brought me up kindly in their own house” when Zeus was overthrowing Kronos.

Boöpis, “cow-eyed,” appears fourteen times in the Iliad alone.

Joan Marler: “Asclepius’s powers to cure and raise the dead were thereby stolen from Medusa.” [Marler, “Re-visioning Medusa: from Monster to Divine Wisdom, add cite]

Tó Dēo: often translated as the Two Ladies or Two Goddesses, this phrase is only applied to Demeter and Persephone. It is a dual plural particular to Greek (it also exists in other, unrelated languages, such as Chinese.)

Relief on women holding up mushrooms, from Pharsalis, a center of the Eleusinian Mysteries

Women holding up mushrooms: This Thessalian funerary relief has been called “Exaltation of the Flower,” but the shapes are wrong, and the stems too wide for the proposed poppies or roses. Pharsalos was a center of the Eleusinian Mysteries, which has led some scholars to identify the women as Demeter and Persephone. Rufus B. Richardson first recognized that they were holding mushrooms in 1911. Among those proposing that these are entheogenic psilocybin mushrooms are Robert Graves, Terence McKenna, and Italian ethnobotanist Giorgio Samorini. For more details see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exaltation_of_the_Flower

On the Eleusinian connection of the place: “Picard notes that ‘one may be increasingly reminded that Pharsalos was indeed an Eleusinian center’.”

Re p. 142: “lest the lady Demeter be angered.” Probably the potnia title was here; i don’t have the Greek text.

p. 146: should read: “by-name Keleos”

The line “dived beneath the lap” could be compared to the Māori story of Maui who climbed up into the vagina of Hine Nui Te Po, which took him to the realm of the dead, not to return.

Typo in caption on p. 149: should read Propylaia.

The story of Baubo’s skirt-lifting is later, or at least recorded later. Iambe is only described as making bawdy jests.

The myth of Demeter vs. Erysikhthon resonates with events in which priestesses incarnate the goddess. The boundaries were blurred in certain ceremonial contexts, or in extraordinary situations. An invading army withdrew when they came across a procession with the priestess of Athena, seeing her appearance as an omen of their defeat.

Legends place Persephone’s abduction in Sicily. [Kerenyi 1951: 241]

Zeus blasting the mortal Iasion for laying with Demeter highlights the severe sexual double standard. It was fine for gods to rape mortals, but not for goddesses to make love with them.

In classical Greek khoiros (“pig”) meant “vagina,” [Keuls, 352-3]

The zodiac was unknown to Greeks before about 300 bce. “Persephone’s weaving, however, may go back to the early Pythagorean-Orphic robe, where it will have symbolized the seasonal progress of vegetation.” [West 1983: 244-5]

Re the Lydian form of Artemis, Artimul. [EB 650.5, in Chadwick, 99] This sounded like an Etruscan ending to me, but their name for the goddess is Artume.

Re p. 130: see my photo essay on these Anatolian pillar goddesses

On Artemis Ephesia

And on the amber pendants of her garland in the Archaic era

Recent scholarship questions the belief that the staring Archaic statues dubbed “Kore” represent Persephone; evidence shows that most of the “Kore” statues commemorate historical priestesses.

Gorgon from Kameiros, Rhodes, circa 600 bce

Gorgons, p 164: Note that the snakes are not hair, but emerge from the Gorgon’s neck as well as the sides of her head, much like the Medusa of Korkyra on p. 165: snakes emerge from her neck and waist.

On p 165, “a knotted snake belt,” see p. 236 for the Gorgon at the Hekatompedon, first temple of Athena.

Athena: Douglas Frame holds, reasonably, that the snake was identified with Athena, not with Erichthonios, which later sources change. Classical myth connects the snake with both Athena and her fosterling, the legendary king Erechtheos (See chapter 4).

The inventories show that Athena’s statue held a gold libation bowl in its right hand, but Frame says that deities were not depicted holding a phiale in this way until about 600 bce. So he asks: what did the archaic statue of Athena Polias hold in her right hand before that? He proposes that her hand was extended in spinning from a distaff. Such an image of Athena spinning is known from Erythrai in Ionia, holding a distaff in each hand. [Frame III.3.15] If this is right, there was a shift from Athena the weaver to Athena the war-lover.

Douglas Frame thinks that Athena changed from a mother goddess to a virgin goddess associated with Zeus sometime around 600 bce. He notes that the Iliad and Odyssey do not describe her as parthenos (a title that first appears in Homeric Hymn 28) and that the Parthenon was a nickname, not an official name for this final temple built on the Acropolis. He argues that Athena Polias was married to Erekhtheos, citing a single custom in which the Epidaurians sacrificed to both of them “in return for statues of the goddesses of fertility and childbirth, Damia and Auxesia.” Frame refers to a scholarly debate over whether the myth of Erikhthonios reflects earlier traditions of Athena as a mother goddess, but he only cites Burkert.

Eva Keuls, on the other hand, proposes that Athenian mythographers invented the “pseudo-maternity” of Athena to give her “some kind of dynastic connection with its early rulers.” [Keuls, 42]

Athena Lindia, her Rhodian form, adheres to the goddess archetypes of Asia Minor

Prometheus creates mankind in the likeness of gods, says Robert Graves: “He used clay and water of Panopeus in Phocia, and Athene breathed life into them.” [Graves, 34. His citations are murky (and often downright inaccurate), but I’ve tracked down a version of this to Hyginus, Fabulae 142]

A predynastic Egyptian C-ware bowl appears to show Neith as a huntress or hunting goddess.

She is holding a bow and arrow (on the left).

Athena Tritogeneia: “to whom Zeus gave birth from his head on the rocky banks of the river Triton.” [Detienne and Verlant, 111] Jane Harrison describes this male birthing of Athena as “a desperate theological expedient to rid her of her matriarchal conditions.” Graves calls Athena “Zeus’s obedient mouthpiece.” [Graves, 46-47]

A late explanation of Athena’s title of Pallas makes her the daughter of “a winged goatish giant, who later attempted to outrage her, and whose name she added to her own after stripping him of his skin to make the aegis, and of his wings for her own shoulders.” [Tzetzes, On Lykophron 355, in Graves, 45-46]

In the words of Euripides, Aphrodite is “greater even than the gods.” [I lost the citation for this, and so could not include it. Possibly from prologue to Hippolytus, or from Antigone.]

Kerenyi (1991: 58) says the love goddess is “the only one of the Titanic generation whose mother is not Gaia.”

Re pp 181-82: Originally Aphrodite’s skirt-lifting is a deliberate act, unlike the Hellenistic trope in which she accidentally lets the cloth drop and scrambles to cover herself. Barber’s proposal that Venus de Milo was spinning would be more convincing if not for the many sculptures that have Aphrodite’s clothes falling off.

Maximus of Tyre writes, “Diotima [in Plato’s Symposium] tells Sokrates that Eros is not the son but the attendant and servant of Aphrodite and in a poem Aphrodite says to Sappho [poem follows]…” [Barnstone, 288 n.152]

p. 185: The speech in which the poet has Aphrodite call her love affair “wretched” and “inexcusable” sounds the theme of female sexual shame, which is repeated in the Iliad’s story of Hephaistos catching Aphrodite and Ares in his bed. The gods all came to laugh at them, while the “lady goddesses” all stayed home “for shame.”

Correction of typo on p. 186: the golden plaque of Ashtart was found in the Uluburun shipwreck.

On the life-spans of nymphai, stags, crows, ravens, and phoenixes: a parallel tradition exists in Ireland, which is mentioned in Witches and Pagans, p. 176.

Frame (online) renders the Linear B inscription as “for Eleuthia, honey, one amphora”]

Alkman gives Othria as Dawn goddess. [Dillon 2002: 214]

Bendis: in Roman period she was also called Oupesia. [Budin, 30] In that same era, Ortheia was called Oupesia. Both of these regional goddesses were associated with Artemis.

More on Greeks assigning their own deity names to foreign deities. Herodotus makes such equivalences in several places: “In Egyptian, Apollo is Horus, Demeter Isis, and Artemis Boubastis.” [Histories 2.156.5] Similarly in Histories 1.199.3 (“the Assyrians call Aphrodite Melitta”); 2.42.5 (“the Egyptians call Zeus Amon”); 4.59.2 (“in Scythian, Hestia is called Tabiti, Zeus . . . Papaios, Earth Api, Apollo Goetosyrus, Heavenly Aphrodite Argimpasa, Poseidon Thagimasadas”) The foreign name appears first in 2.144.3 (“Osiris is Dionysus in the Greek language”). Elsewhere, Herodotus says that among Scythians, Gaia is the wife of Zeus.

Nevertheless, Greek men considered it low-class and effeminate, as they did the sikinnis (“shaking”) dance, said to have been named after a Phrygian priestess of Kybele. Its dancers shook, whirled, stamped, crouched, and leaped. Gay or trans males were commonly called kinaedi, from Greek kinein, “buttock-shaking.” The hip-swaying saulomenos dance was also favored by goddess devotees and courtesans, who “float along with a tremulous motion of the loins,”according to Randy Conner and by the Galli, trans priests of Kybele in feminine robes, headdresses, and makeup. According to reports by Greco-Roman men, some cut off the male genitals in offering to Kybele in their ceremony of initiation. Some sources portray the Galli as the leaders of her religion.

To their south, at Comana in the Taurus mountains, the black-robed votaries of Ma whirled with unbound hair to the music of drums and trumpets. In ecstatic frenzy, some struck themselves with blades, sprinkling the goddess with their blood, and prophesied in the spirit of “the great goddess of the two Comanas.” As in the mysteries of Kybele, gender-variant priests were prominent.The Romans called these euphoric celebrants fanatici, which originally meant “those of the fane (shrine).” Their negative interpretation of these intense rites produced the modern word “fanatic.” The great “golden” temple of Ma was ruled by a high priest of the royal dynasty, second in rank only to the king. The temple owned great estates and was staffed by thousands of hierodules, temple servants. This huge city-temple was known as Hierapolis, “holy city.” It is hard to make out where the Anatolian priestesses stand in this picture. Classical sources record little of them; Roman accounts pass over women’s spheres of power. But the women are barely visible, and appear to be eclipsed.

In Samothrace, a 36-meter long freeze depicted some 200 maidens, wearing the polos headdress, dancing on tiptoe to honor the Great Goddess of the Mysteries. It was sculptured around 340 BCE. “The dancing must have been a spectacular part of the rite. Dressed in their ritual garb and performing in front of the hundreds of mystai who converged annually on the island, dancing on their tiptoes in the swirling lines must have been the high point in the religious life of the Samothracian maidens.” [Dillon 2002: 48]

Budin’s The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity (2008) considers this subject in depth, most convincingly for Greece, less so for Mesopotamia. Also see a review of this book by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2009/2009.04.28/ Other key sources are S. M. Baugh. “Cult Prostitution In New Testament Ephesus: A Reappraisal.” JETS 42/3 (Sept 1999) 443–460; and the work of Julia Assange, including “The Kar.kid / Harimtu: Prostitute or Single Woman, A reconsideration of the evidence.”

Romans certainly sensationalized the castrati priests. But written references and the stela portraits of hierophants do appear to be disproportionately devoted to male-to-female priests. If the Galli first joined the women, they ended up displacing them in public ritual leadership.

“I have heard it foretold, that one day the Athenians would dispense justice in their own houses, that each citizen would have himself a little tribunal constructed in his porch similar to the altars of Hekate (Hekataion), and that there would be such before every door.” [Aristophanes, Wasps 804 ff]

On Cretan initiation into the Mysteries being open to all, after publication I found a source I wasn’t able to locate before. It is from Diodorus Siculus (5.77.3–8):

Such, then, are the myths which the Cretans recount of the gods who they claim were born in their land. They also assert that the honours accorded to the gods and their sacrifices and the initiatory rites observed in connection with the mysteries were handed down from Crete to the rest of men, and to support this they advance the following most weighty argument, as they conceive it: the initiatory rite which is celebrated by the Athenians in Eleusis, the most famous, one may venture, of them all, and that of Samothrace, and the one practised in Thrace among the Cicones, whence Orpheus came who introduced them—these are all handed down in the form of a mystery, whereas at Knossos in Crete it has been the custom from ancient times that these initiatory rites should be handed down to all openly; and what is handed down among other peoples as not to be divulged, this the Cretans conceal from no one who may wish to inform himself upon such matters. Indeed, the majority of the gods, the Cretans say, had their beginning in Crete and set out from there to visit many regions of the inhabited world, conferring benefactions upon the races of men and distributing among each of them the advantage which resulted from the discoveries they had made. Demeter, for example, … Aphrodite … Apollo … Artemis … And similar myths are also recounted by the Cretans regarding the other gods, but to draw up an account of them would be a long task for us, and it would not be easily grasped by our readers. (trans. Oldfather 1939, modified.) [From 4: The Cretan Contexts https://archive.chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/5102.4-the-cretan-contexts]

Chapter IV: Mythic Conquests

Thetis: a scholion on Prometheus Desmotes says that Zeus was pursuing Thetis through the Caucasus mountains, but Prometheus stopped him. [Gantz, 162]

Metis: In one version, Zeus talked her into turning into a fly which he was then easily able to swallow. Or, he convinced her to have sex once more and gulped her down while she was in the throes of orgasm. “But he seized her with his hands and put her in his belly; therefore did Zeus… swallow her down suddenly.” [Theogony 929]

Poseidon went into a rage and sent a flood. To placate him, the men instituted new laws: “The women must lose the vote, no child shall take the mother’s name, and they themselves cannot be called Athenian [citizen] women.” [Zeitlin 1996: 116. The quote comes from Varro’s lost De gente populi Romani, as recorded in Augustine’s De Civitate Dei 18.9]

According to the Orphics, Zeus raped Persephone too. Demeter had hidden her daughter in a cave and put the dragons that pulled her cart to guard her. But Zeus turned himself into a huge serpent and broke into the maiden’s chamber. He impregnated her with Zagreus, a Thracian form of Dionysos. [Dionysiakōn VI, 157ff, in Olmsted, 275]

The same crushing of female power manifests when the Spartan king Tyndareus puts fetters on Aphrodite Morpho “to symbolize by these bonds the fidelity of women to their husbands.” [Pausanias 3.25.10, in Frazer 1913: III, 157]

Athena’s attitude: She takes a patriarchal woman’s classic path to power, supporting the lordship of her father, and clinging to her own exceptional status. She is not like the other women. Strangely, Athena and Artemis, both marriage resisters, as well as half-sisters, have little to do with each other.

Munson (2005) interprets the “stuttering” of Battos as an allusion to his marginal status as “not fully Greek,” since he is the son of a Theran and a Cretan concubine. She views the problem with his voice as “really one of language.” She adds that “Scholars currently tend to think that the native populations played a more important role in Cyrenaica than in other areas colonized by the Greeks.” (Citing Laronde 1990.48. Giannini 1990.70–71)

Lokrian maiden tribute to Troy. These girls must be led to the goddess secretly by night, while the Trojan men hunted them down. Maidens killed attempting to reach the safety of the temple were to be burned with wood that bore no fruit, and their ashes cast in the sea; those who arrived unharmed had to remain in the sanctuary for life, barefoot and wearing only a simple shift, sweeping out the temple and performing other menial duties like slaves. They grew old as virgins, and when one died, another must be brought to take her place. Larsen 2007: 51

The journey of the Lokrian Maidens has been interpreted as a ritual counterpart of the many myths in which adolescent girls give up their lives to save their cities; it has also been called an “exemplary initiation,” by which a few members of an age cohort stand in for the whole group in performing acts symbolic of that group’s passage to adulthood. Finally, the putative humiliation of the maidens and the casting of their ashes in the sea are characteristic of the scapegoat or pharmakos rite, in which a city wards off harm from itself by expelling individuals who are treated as carriers of pollution. [Larson 2007: 51]

All these stories of maiden sacrifice seem to get lost in Herodotus’ catalogue of “barbarian” societies who, according to him, practice human sacrifice. Munson (2005) enumerates: “Human sacrifice is also perhaps recorded for the Persians at 7.180, and see 1.86.2. It is otherwise a custom only in Herodotus’ ethnographies about Massagetae (1.216.2), Padaean Indians (3.99), Scythians (4.62, 71–72), Taurians (4.103), and various Thracian tribes (4.94, 5.5, 9.119). It is normally regarded, at any rate, as a quintessentially barbarian practice: Plutarch On Superstition 171B–E and Nikolaidis 1986.138.”

West 1983: 87-88 notes that the Orphics sometimes call Phanes “Metis.”

In Orphic accounts, Zeus not only raped his sister Demeter, engendering Persephone, but he went on to rape his daughter too. Demeter hid Persephone in a cave and placed the dragons that pulled her cart to guard her. But Zeus turned himself into a huge serpent and broke into the maiden’s chamber. He impregnated her with Zagreus, a Thracian avatar of Dionysos. [Dionysiakōn VI 157ff, in Olmsted, 275]

In the Orphic Rhapsodies, Zeus swallows his great-grandfather Phanes, while in the Derveni Papyrus he “swallows either the phallus of Ouranos or the whole body of Protogonos.” I’m quoting from Meisner (80-81), who discusses a dispute over how a key term in the Derveni Papyrus should be translated: does the word aidoīos signify “phallus” or “revered one.” And, does it refer to Ouranos or Protogonos?

Spartans claimed that the Messenian general Aristomenes and his men kidnapped Lakonian maidens from the border sanctuary [Larsen 2007: 106] but others said that this was a pretext for invasion, and that the Spartans dressed up as maidens to justify their attack.

Euripides calls Taugete “the titanis daughter of Merops,” the king of Kos island, which conflicts with her usual descent from Atlas and Pleione. [Helen, in Battezzato, 147] This renaming probably relates to her sister Merope, another of the Pleiades. Several stories have Artemis punishing the daughter or wife of Merops. For insulting Artemis, his daughter Byssa was changed into a seabird (byssa); or his wife Ethemia refused to worship Artemis, and ends up in Hades, still alive. [Battezzato, 148-49]

The heroine Hippodamea (“Tamed Horse”) escapes her father’s control when her future husband wins her in a race. Horse-named women run through Greek myth, especially for Amazons, prophetic women, and ancestral mothers.

The outcome of Melanippe the Wise is lost, along with most of the play and apparently all of its sequel, Melanippe the Captive. In a surviving fragment from Euripides, a man urges other men to severely punish Melanippe, and not hold back because they are kin to her, because it is paramount to prevent other women from being influenced by her “transgression” (of having been raped). [Fr. 497, in Karamanou, 156; and McHardy, 4] And as other sources inform us, this is what happens; Aeolos cruelly blinds Melanippe and locks her up underground. [Hyginus, Fabulae 186]

Rape apologia in HellenicGods.org: “To escape his advances, Demeter transformed herself into a snake. Zeus partook of this dance” and turned into a snake too. “The two enwrapped themselves into a knot of Hercules, producing the Daughter (Kore) who became the mother of Zagreus.”

Here’s another example of mendacious excuses for sexual violence: “but Castor and Polydeuces being charmed with their beauty, carried them off and married them.” [“Leukippides,” in Encyclopedia Mythica. pantheon.org/articles/l/leucippides.html.

On Deō being “ravaged in her copulation”: it’s not clear what etymology they’re drawing on here, to come up with that comparison.

Zas placing beings in the “recesses” of Kthonie compares to Ouranos forcibly confining the first progeny of Ge within her body.

Rape culture and the actuality, were and are mutually reinforcing systems. New rape stories kept being added, and reiterations of the old ones were endlessly reproduced by later artists, in the Renaissance, Baroque, and Romantic eras, even up to the present. Bernini, Rubens, etc.

On the Serpent Knot:

Hellenistic diadem with Snake Knot, NY Met

Diadem with Heraklean knot, Pontika, Ukraine, 300 bce

Color photo of the Snake Knot armband pictured in Chapter IV.

The dragon goddess Delphyne surfaces again in the myth of Typhoeus.

“At Castabala, in Cappadocia, the priestesses of an Asiatic goddess, whom the Greeks called Artemis Perasia, used to walk barefoot through a furnace of hot charcoal and take no harm.” from Frazer, James (1955) The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. London: Macmillan, Vol. XI, p. 14

The story of Andromeda is placed in Aethiopia, but Greek vase paintings never depict Andromeda as African, though she is shown among Africans. By some accounts she is chained to the rocks at Jaffa in the Levant.

Chapter V: Pythias and Melissae

Pausanias concurred, but uses the name Paphia, either a garbling of Pasiphae or a reference to Aphrodite of Paphos: “People consult it by sleeping; and of what they desire to know, the goddess sends them dreams.” [Pausanias, 8.53.7] These are both definite about Aphrodite and no reference to dreaming. [Cannot find this passage in search]

Themis: Her name comes from the same root as the English doom, which originally meant “judgement,” then “fate,” and eventually narrowed to the meaning “downfall” or “death.”

Pythagoras: Iamblichus recorded the Pythia’s prophecy that his pregnant mother would bear a holy child. She named her son after the Pythia (translating Pythagoras as “spoken by the Pythia.”)

It has been suggested that the Labyades priesthood at Delphi was originally named Labryades after the labrys. [Was this from Robert Graves?] Seems philologically unlikely.

Scheinberg (14-15) disputes any connection between the bee-nymphs and the thriai, since the latter are not explicitly named in the Hymn to Hermes. She reads semnai (“venerable”) in place of the thriai associated with the divination pebbles, and argues that there could have been more than one triad of nymphs on Parnassos. This seems unlikely, since both the thriai and the bee-women are associated with prophetic power. Philokhoros, as she herself cites (8) states that the three nymphs on Parnassos found the mantic pebbles which were then named after them. There no reason to distinguish these groups of nymphs from each other or from the Korykian nymphs who live on the same mountain. More to the point, Scheinberg’s position is a minority view; Jennifer Larson (“The Corycian Nymphs and the Bee Maidens of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, 1995) sees the Thryiai as identical to the nymphai of the Korykian Cave, and so does Jeremy McInerney (1997: 268)]

Herodotus has an interesting story, the only one of its kind, about a Boiotian oracle of Apollo who was consulted by the Karian Mys. The oracle began to speak in a foreign language which the recorders couldn’t understand. Mys seized the tablet and began writing, saying that it was his Karian language. [Histories 8.135.1-3]

Plutarch, a priest who observed the prophetesses up close, supposedly said that the Pythia’s life was shortened by the intensity of her spiritual exertions. At the end of each trance, she would be panting, like a runner after a race, or a dancer after moving for hours. [Plutarch De defectu oraculorum, online] I looked at this twice and cannot find such a quote. Perhaps an error in a source that mistook a passage from Lucan.

Herodotus (1.65) already refers to the Pythia’s prophecy in hexameters.

p. 274, “in the purple” just as likely to be dark red or magenta, from the famed murex dyes of the Phoenicians.

p. 279: error: reference to “Chapter 2 frontis” should read “Chapter 1 frontis”!

p. 280: “around a horned altar” reminds of the horned altars of the Cretans, and also the Delian altar of horns, sacred to Artemis.

p. 294: For more on women’s ceremonial fillets, see Vol II, Book 2.